Surfacing Narratives Towards Transitional Justice in the North and South:

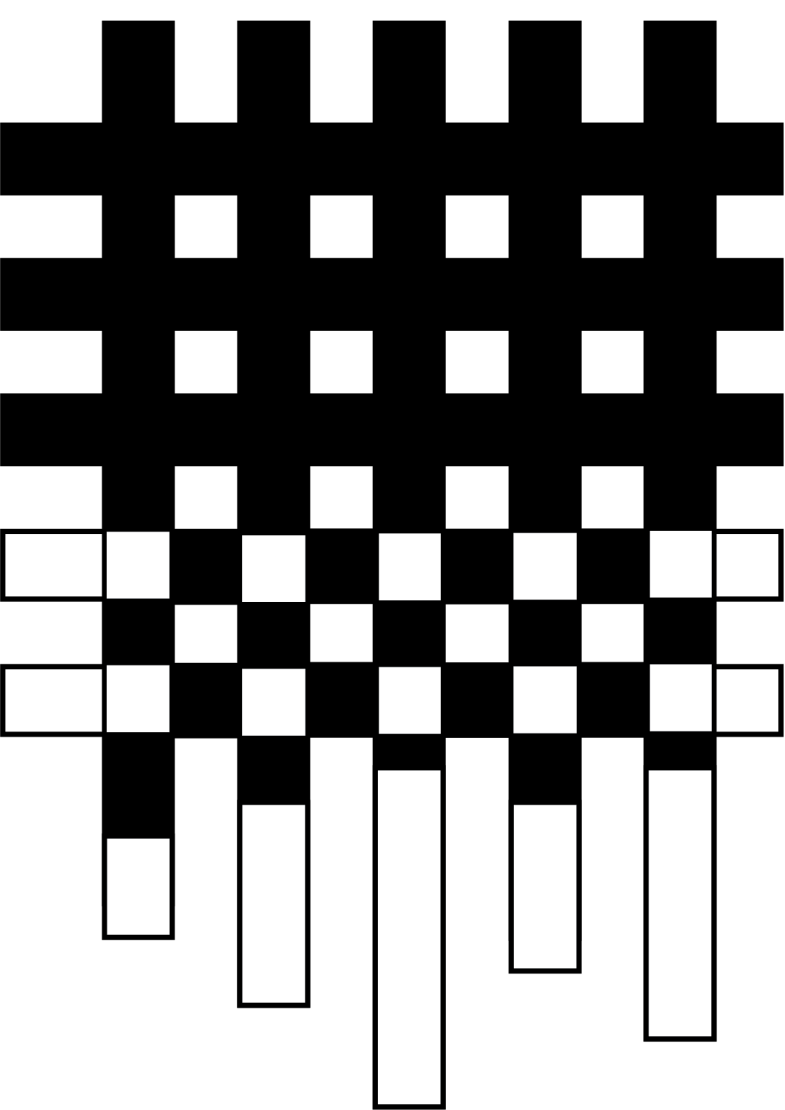

Weaving Women’s Voices – A Memory Project in Aid of Developing Transitional Justice Interventions

Women of Palimbang

Women of Palimbang

“Di ta den katawan ugeyd na katawi ka den I timpu na Martial Law.”

I don’t know but what we do know was that it was the period of Martial Law.

From Ebok Mangakoy, 2021

Memories of the Martial Law period are greatly polarized given people’s diverse experiences during the 1970s. For the people of Malisbong, a village in the town of Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat, their memory of Martial Law will always be associated with the violent annihilation of their town. Rather than remembering their community’s celebrations of Ramadan, the villagers of Malisbong recall 24 September 1974 as the day when they personally experienced the violence of Martial Law.

Early that day, helicopters and planes threatened their town as it flew and dropped bombs over their homes. In the afternoon, ten naval boats docked at their coast and fired cannons at their quiet village. As explosions deafened the screams of the villagers, it was increasingly clear to the residents of Malisbong that the violence that has pillaged many Muslim communities in Mindanao had finally come to their town.

The brutality under the Marcos presidency was widely known among the people of Palimbang. Stories of Ilaga were familiar to many yet everyone hoped their town would be outside of their radar. After all, the Muslim residents of Palimbang lived peacefully with Christians. The harmonious relationship between these two religious communities offered hope during this perilous period. These military men, however, were in search of “Blackshirts,” an emerging Muslim militia who fought against violent Christian groups such as the Ilaga. The sudden bombardment of their town affirmed the state’s brutal desire to seize and control Muslim people and their land. This savagery operated beyond immobilizing the town of Malisbong through military barrage. For the women of Malisbong, this merciless attack also entailed the destruction of their community as men were viciously murdered in their town’s most sacred space, the H. Hamsa Tacbil Mosque. The devastating loss of countless husbands, brothers, and sons in the community would be forever engrained in the minds of many women in Palimbang. As seen in the words of Ebok Mangakoy, one of many female residents of Malisbong, the bombing of their village marked a strong memory of the violence of Martial Law and how it would tragically transform the shape of their community and the sanctity of their lives. The stories of the women of Malisbong carry social memories of state violence unto Muslim communities in Mindanao. At the same time, it would showcase structures that left many of these women under the cruel mercy of Marcos’ henchmen.

Addressing the “Moro Problem” in Mindanao

In a public address in 1979, Cagayan de Oro statesman and Marcos critic, Reuben Canoy, raised the issue of the “Moro Problem,” to which he described as the reality that “Moros constituted a nationality distinct from, and older than, that of the Christian Filipinos (Canoy 1979, 296).” The use of the term ‘Moro’ to highlight the colonial and discriminatory roots of this issue. Since Spain colonized the Philippines, gaining control of its resources entailed controlling its peoples. For the resource-rich Mindanao, this meant that the Spanish needed to control its indigenous people and Muslim communities. It was not long before Muslim leaders waged wars against the Spaniards who were concerned in taking over Muslim land while also converting their faith (Gowing 1980; Canoy 1979, 296–97)(INSERT SAMUEL TAN). The overlaps between religious discrimination and state expansion would be sustained for hundreds of years, across different colonial structures and political leadership (Gowing 1980; Abinales 2000). As such, the Muslim community, particularly those residing in Mindanao, have a long history against state prejudice.

By the time Ferdinand Marcos was elected president of the Philippines, the “problem” in Mindanao remained unsolved. If anything, the “problem” escalated as Marcos empowered people and structures that enforced all forms of violence unto various Muslim communities. The story of Manili showcased how the Marcos government enabled the vicious massacres and raids of the Ilaga. Even within state structures, the Marcos government would also intentionally compromise Muslims who worked for and with the nation. Such was the case of the Jabidah massacre where 180 young Muslim Tausug soldiers were massacred in Corregidor, Bataan in 1967. Veiled as guerrilla training for the covert military mission “Operation Merdeka” which aimed to “liberate” Sabah from Malaysia, these men stepped inside the thick woods of Corregidor and never got out. Survivors claimed that a mutiny in the camp happened, leading to tensions that pushed the indiscriminate killing of the young Muslim trainees (George 1980, 125–28). Further investigations showed the mismanagement of military officers who squandered funds by splurging the budget in night clubs in nearby Roxas Boulevard while recruits were deprived of pay and decent food. The Tausug recruits signed a petition and used it to threaten the military officials. Those who signed the petition were eventually targeted for execution. Those who did not were eventually reassigned to other units of the armed forces. Not one of the officers were held accountable as the event was not recognized by the Philippine military. It took forty-five years before the Philippine government acknowledged the violent incident as a massacre under President Benigno Aquino III on March 18, 2013.

The Jabidah Massacre is a watershed event in Philippine history that would take the relationship between the Philippine State and the Muslim community in Mindanao towards a more violent turn. The massacre would reverberate throughout the Muslim communities in Mindanao and would spark calls not for justice but for independence and consequently, separatism. The legitimacy and acquiescence they previously conferred on the Philippine government would be obliterated by this betrayal and would never be restored up until today. In corollary, Muslim leadership would pass on from traditional royal families, whose ties with the central government was a source of blame, to young intellectuals with revolutionary fervour such as Nur Misuari. Moreover, the event pushed Muslims to think in terms of a larger community of Muslims, ummah, in contrast to those outside the faith. Such conceptions were the result of greater integration of Filipino Muslims into the outside world. In the late 50s and 60s, Muslim missionaries from other countries began doing work in Mindanao and later promising students were sent to Islamic universities abroad for education and religious training. This evolving ideology proved to be the basis of resistance against the Marcos regime—a reminder that Islamic faith became the rallying identity that resisted Western colonization in many parts of insular Southeast Asia in the early modern period. As members of the Muslim communities in Mindanao rallied together after the Jabidah Massacre, they formed the group Muslim Independence Movement which eventually became Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM).

The MIM emboldened the Muslim community who now dreamt of independence from the oppressive Philippine state. The formation of MIM gave Muslims political presence which brought great fear among Christians living in Mindanao. It did not help that the Marcos government labelled this separatist movement as “communists”. While some Christians fled to other parts of the country, others chose to take violent measures which led to bloodshed between Christians and Muslims in many towns in Mindanao. These ruthless actions motivated MIM leaders to lobby for their political causes (George 1980, 133–36). For some members of the MIM, retaliation against these religious tensions entailed private armies that would strengthen their community and protect its leaders. Rumours of private armed militia called “Blackshirts” became associated with MIM. Their presence escalated the violence in Mindanao as they were increasingly flagged as terrorists by the state (Gowing 1980, 193–94). The Philippine government gave the military and the constabulary full authority to savagely hunt these groups of armed Muslims and mercilessly eradicate them from Mindanao (George 1980, 139–41). The search for “Blackshirts” was indiscriminate and cruel. This attention would eventually be directed to the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), a separatist organization led by young Muslim intellectuals such as Nur Misuari. Civilian communities in Mindanao, many of which were Muslim like Manili, became casualties of war.

Naval boats on a peaceful coast

Understanding the massacre at Palimbang entails looking back at the activities of the MNLF. In March 1973, MNLF forces attacked both Jolo, Sulu and Cotabato City. While the military was able to thwart the MNLF attack in Jolo, the same could not be said in Cotabato. Under the command of Hashim Salamat, one of three founding members, the MNLF was able to overrun the city. The aim was to capture both locations to declare an independent Moro state, the ultimate aim of the rebellion. According to commander of the Central Mindanao Command, military forces were pinned down in a tiny corner in Awang and chose to secure the airport to await reinforcements. With the Air Force providing close ground support as well as airlifting reinforcements, war material and supplies, and evacuating the wounded and the dead, the military was able to deflect the offensive (Abat 1999; 1993). The attempt to duplicate this feat was initiated the following year. In February of 1974, MNLF forces overrun Jolo, Sulu. This time they were more successful. The city was taken over completely and the military had to withdraw.

Conflagration brutally came next. Intent on retaking the city and avenging their humiliating loss, the military deployed naval vessels to bombard the city and deploy fighter jets using napalm. The result would become known as the so called 1974 Burning of Jolo. The military expected a similar attack in the mainland, and that would be Cotabato where the MNLF was strongest. Since the topography of the city is located on a large river that juts to the sea, it is necessary for the military to deploy naval assets. During the 1973 attack on Cotabato city, the MNLF surprised the military by displaying amphibious assaults. A few years back, arms shipments from abroad, mostly from Libya, landed on the shores of Cotabato. The armaments that arrived scared the military as they were better and more modern than those issued by the Armed Forces.

Palimbang also became a victim of this conflict because of its location. The town was beside Lebak, the main depot and supply base of the MNLF. It is believed that the shipment of Libyan arms in 1973 took place in Lebak. Since both Palimbang and Lebak are coastal towns, military naval assets patrolled the area. The acting governor of Cotabato province at that time, Gov. Gonzalo H. Siongco, was a brigadier general in the Philippine Army. He replaced the former governor, Col. Carlos B. Cajelo of the Philippine Constabulary. The Marcos government appointed these military officers which placed the entire Cotabato province under military rule. Thus, when the military received news that MNLF rebels were massing up in Palimbang, the response was furious. Their assault in Palimbang was meant to prevent a repeat of the previous year’s daring attack that almost succeeded. It was logical for the military to deploy four army battalions and numerous naval assets in Palimbang. It was also strategic to separate and detain women and children on ships while they gunned down the adult men in the community.

Isolated vulnerable women

To the residents of Malisbong, the military bombardment of their town was illogical. The assault of canons and bombs in the afternoon of 24 September 1974 did not make sense to the townspeople who were at ease with their quiet lifestyle of farming coconuts, logging, and fishing. Homes fell and coconut trees were ablaze as bombs continued to strike the town. Residents madly scrambled for safety as some stayed behind to protect their children and loved ones while others hurried elsewhere to move away from the fire (Piang 2021). Residents from nearby villages, who were also looking for safety from the air raids and bombardment, unfortunately found themselves in the chaos of Malisbong (Llana 2021; Piang 2021). Rather than ensuring the safety of the village, the military barrage only brought pandemonium.

There was also nothing strategic in separating the adult men from the women and children, more so in a community where men bear the greater responsibility of providing sustenance and strength to their families. As soon as the explosions stopped, soldiers started isolating the adult men in the community. Adult men were led towards the mosque while women and children were gathered in the town of Malisbong.

Ebok Mangakoy was a resident of Malisbong and was pregnant with her second child when the military assaulted their town. She had no idea why the military attacked but she remembered that the soldiers looking for blackshirts (Mangakoy 2021). She recalled how the women and children were mobilized not just by the military but also by local officials. She said,

“Bale inangayan kami na kagawad ka mag surrender kami kun ka makauli kami bun sa mga malulem nay a nami kinaladas na alas tress a malulem. Ya nin pdtalu na “baba kanu kpidtalu na mga sundalo ka amag antu na baguli kanu bun”. Inunta na nakalabi sapulo gay kami den na da kami pan makauli. Ya kinauma na sapulu gay enggu telu sa mapita-pita na tig nilan “su langun na mga mama na timun” bale pina line su mga mama sa angga telu-telu ka taw. Bale tig nilan na “sekanu ah mga babay na pagalugan kanu” na nagalugan su mga babay sa pita-pita ka bagiten su mga mama sa masgit ni kagi Kamsa. Ya mauli santu na inipangidtug nu mga sundalo su mga pegken ka da nilan pakana su mga mama. Pidtalu na mga sundalo antu na “sekanu ah mga babay na pageda kanu sa Naval” bale ya name kinapageda sa Naval na mg alasingko na kalalamagan na nan kami sa kaludan. Su mga mama mambu na lu den sa masgit kinulung nilan.

(A deputy official came to us in the mountains and told us to surrender since we should be able to return home by the afternoon. He said, ‘the soldier said you should go down since they’ll eventually let you go’. That said, we stayed there for more than ten days and they refused to let us go home. By the thirteenth day, the soldiers told us, ‘You ladies should prepare food for the men’. That’s what happened since the women cooked around dawn because they were going to bring it to the mosque of Kagi Kamsa. At that time, the mosque was still unfinished. When the food was cooked, the soldiers threw them away and it was not sent to the men. And then, the soldiers said, ‘you ladies should ride the naval boats’. From five until the next day, we were offshore (Mangakoy 2021).

The call to surrender was a vivid memory for Ebok who shared that the reason why the deputy official told them to surrender was “Na agiya kena kami bagunut sa malat ah taw, bale endaw I ped-surrender nay a nin mana na kena bagunut sa malat ah taw (Because we did not participate with bad people, because whoever surrendered meant that they were not aligned with people who have ill will).” In surrendering, the women were admitting their innocence. In demanding their surrender, the soldiers already viewed these innocent women as their enemies.

This prejudice was also recalled by some women who remembered these soldiers’ instructions differently. Rather than being instructed to cook for men, some women vividly remembered begging soldiers to allow them to prepare food for their husbands and brothers whom they knew were imprisoned in the mosque. Amina Gunao begged soldiers to give the food she prepared for her husband. The officers gave her a glimpse of hope as they brought her husband out. All hope was lost, however, when the soldiers shot her husband in front of her. She recalled the soldier saying, “patay kayong lahat (you will all be dead).” (Mangansakan II 2016). The soldier’s response highlights the true intent of the soldiers who only wished death upon their community. An act that was symbolic of women’s filial duty, cooking did not offer any form of security for the Muslim families in Malisbong. This made the women helpless, showing their powerlessness against the soldiers.

Similar to the Maguindanaoan Muslim community in Manili, the town of Palimbang is highly patriarchal. Men were given greater mobility that allowed them to afford education, resources, and opportunities that can help uplift their families and communities. Women supported their family through domestic work and moral education. The community’s patriarchal order takes root in their Islamic faith that has shaped their community’s beliefs and practices for hundreds of years. The forceful military disruption of this patriarchal order left the women of Malisbong isolated and vulnerable to violence.

Seeing that their filial actions were futile, the women of Malisbong yielded to the soldiers who were exercising absolute control over their community and their lives. They followed the soldiers’ command to board the naval boats Mactan and Mindoro. Residents also had recollections of the military command who sieged their town–the 15th Infantry Battalion. As women boarded on boats, the men of Malisbong remained in the mosques.

Little did the women know that this would be the last time they would see their husbands, sons and other patriarchs in the community. After all, leaders in the community who were cooperating with the soldiers consistently promised them that they would return soon. As such, with little hope left, the women rode the naval boats along with other children in the community. Ebok tried to recall if something happened to her onboard the naval boat, “Na da bun, uged na su tinaguwan nilan sa lekami na gaagag kami. Na sa baba nantu ban a su bagiganan na mga sundalo na ya nin pagubay na su mga kalabaw, sapi, kambing. Bale sekami na siya kami sa pulo bale putaw na mayaw ka gaagag kami…. [P]inangenggan kami nilan bun sa mga bisquit. Na sakabiyas ah mga sundalo ka aden mga pamalang nilan. (Nothing happened but we were placed at a part where we were exposed to the sun. Underneath where we stood was the sleeping quarters of the soldiers who shared that space with carabaos, cows, and goats. As for us who stood above, we were standing on steel, so it was very hot and we were scorched….[T]hey also gave us some biscuit. Those soldiers had ear piercings)(Mangakoy 2021).” Ebok’s experience on the naval boat was a lot fortunate compared to others who died from heatstroke or dehydration. Lasina K. Abdullah lost one of her five children on one of those naval boats due to dehydration (Calamba 2016). The experiences of the women on the military naval boats varied as some were held captive for a day while others took two. Ebok remembered a conversation on the boat between a certain Captain Payumo and the ex-mayor of their town, Kagi Dros, where she heard “su mga babay na ibpalen nu (bring down those women) (Mangakoy 2021).” These women could not remain on the boat forever. The soldiers needed to move the women as far away from Malisbong where the men were already being massacred within and around the mosque.

According to the American Passionist priest assigned at the neighbouring town of Milbuk, Art Amaral, the situation in Palimbang was dismal. Assigned as a civilian liaison to help the evacuation of women, Amaral witnessed the violence of the military and the vulnerability of the women in their hands. Amaral remembered a conversation with a Colonel Molina who asked him, “Let me ask you, Father… is it better to feed them or to kill them?” while referring to many Muslim men who were imprisoned in Malisbong’s mosque. The question spurred a short debate where the priest was adamant about saving the men, stopping this cycle of vengeance with Muslims. Colonel Molina was unconvinced (Amaral 2015, 209).

The town of Kulong-Kulong served as the refugee centre for the women of Malisbong where the military troops were supposed to give them food and shelter. Amaral assessed the town and made provisions for the incoming refugees. Along with his team of volunteers, many of which were Catholic Manobo women from his parish, they coordinated with the community of Kulong-Kulong by preparing the basic necessities needed for this influx of refugees, from water to sanitation (Amaral 2015, 227–28). These preparations were far from ideal. Despite the efforts of the Kulong-Kulong community and nearby towns, the evacuated of Palimbang hardly received any support. If anything, the women remained vulnerable under the military who would use force to satisfy their own personal needs.

Ebok recalled how her family did not receive any support when they arrived at Kulong-Kulong. She shared that some women survived by using what little money they managed to bring or by harvesting bananas with the help of the military (Mangakoy 2021). Bernie Bandala shared how his mother sold their family’s properties to soldiers in order to ensure their next meal and safety (Calamba 2016). For some soldiers, material properties were not sufficient. Some soldiers wanted absolute control of women’s bodies.

Submission to new patriarchs

As the days continued in Kulong-Kulong, women became increasingly vulnerable to men. Soldiers took advantage of women’s desperation and used food as an opportunity to abuse women. Accounts of sexual abuse were rampant in the refugee centre (Llana 2021). Bernie heard of a woman who was sexually harassed by a soldier in a fishpond. Out of shame, the woman killed herself with scissors. In another account, Abu Bayao shared how his sister, Hadji Fatima, were locked in a big warehouse with other young women by Captain Payumo who needed to take this measure to protect the young girls from being sexually violated (Calamba 2016).

For women with no access to money and property, their bodies became their ticket to safety and survival. Bayol Maguiales shared her account of befriending one of the soldiers in the refugee camp. At this point, Bayol had not eaten for days and asked for some rice from her friend. The soldier gave her some NHA rice and proceeded to help some of her requests, one of which involved seeing her father in the mosque. The soldier accompanied her but not without sexually violating her in return. Bayol was helpless. Despite their faith’s value on women’s purity, Bayol continued her relationship with the soldier out of sheer need to survive. Her courage to survive came with great trauma (Calamba 2016; Mangansakan II 2016).

Given the power soldiers had on the refugees, some women turned to soldiers for their safety. Some used marriage as a route to secure their family’s security (Piang 2021; Abdul 2021). Napis Abdul was not in Malisbong during the assault but soon found herself embroiled in a situation where marrying a soldier ensured her safety. Soldiers were rampant in Palimbang since the bombardment of the coast. A particular soldier, who frequently drank in her relative’s house, took a great liking to her and was trying to force himself unto her. Unable to resist against the soldier’s exhortation, her family found it wise to submit to the soldier’s whims, even when the soldier had no powerful position in the military. The soldier gave her family no dowry nor did he provide any form of sustainable support during their marriage. When their family returned to Manili, her relatives also encouraged other women to marry soldiers for their safety (Abdul 2021). As Napisa shared,

“Bale inangayan kami na kagawad ka mag surrender kami kun ka makauli kami bun sa mga malulem nay a nami kinaladas na alas tress a malulem. Ya nin pdtalu na “baba kanu kpidtalu na mga sundalo ka amag antu na baguli kanu bun”. Inunta na nakalabi sapulo gay kami den na da kami pan makauli. Ya kinauma na sapulu gay enggu telu sa mapita-pita na tig nilan “su langun na mga mama na timun” bale pina line su mga mama sa angga telu-telu ka taw. Bale tig nilan na “sekanu ah mga babay na pagalugan kanu” na nagalugan su mga babay sa pita-pita ka bagiten su mga mama sa masgit ni kagi Kamsa. Ya mauli santu na inipangidtug nu mga sundalo su mga pegken ka da nilan pakana su mga mama. Pidtalu na mga sundalo antu na “sekanu ah mga babay na pageda kanu sa Naval” bale ya name kinapageda sa Naval na mg alasingko na kalalamagan na nan kami sa kaludan. Su mga mama mambu na lu den sa masgit kinulung nilan.

(A deputy official came to us in the mountains and told us to surrender since we should be able to return home by the afternoon. He said, ‘the soldier said you should go down since they’ll eventually let you go’. That said, we stayed there for more than ten days and they refused to let us go home. By the thirteenth day, the soldiers told us, ‘You ladies should prepare food for the men’. That’s what happened since the women cooked around dawn because they were going to bring it to the mosque of Kagi Kamsa. At that time, the mosque was still unfinished. When the food was cooked, the soldiers threw them away and it was not sent to the men. And then, the soldiers said, ‘you ladies should ride the naval boats’. From five until the next day, we were offshore (Mangakoy 2021).

Given the community’s lack of power over the armed soldiers, women like Napisa turned towards the soldiers who were the new patriarchs of the community. Soldiers soon commanded their lives as they were integrated in the community through marriage. Some were conscientious to embrace the Islamic faith and abide by its rules (Lison Sr. 2021). Other women accompanied their husbands when they returned to their provinces (Piang 2021). Napisa’s husband, however, conveniently used their marriage during the five years he was stationed in Malisbong. After building a family with Napisa with the birth of their son, Napisa’s husband left the community to pursue further study in the army. Since then, Napisa’s husband has not returned nor has he made efforts to contact his family. Despite the promise of seeing a secure future with her military spouse, Napisa garnered no benefit from her marriage. While not all shared the same fate as Napisa, her story highlights how soldiers used the community’s vulnerability for their own gratification. Given the absolute loss in Malisbong, women were compelled to find stability through marrying the men who controlled their community and their bodies.

Recovering what was lost

The massacre at Palimbang is very different compared to the violence that happened in Manili. The viciousness and brutality of the incident at a date so close to the declaration of the Martial Law have left the community traumatized. As seen in Ebok’s quote above, the only thing that made sense about the brutality of that period was that it was period of Martial Law.

Studies on Martial Law had shown the many questionable actions of the Marcos government. In fact, the Palimbang Massacre is unusual due to various factors that make it stand out compared to the other massacres that occurred in Mindanao at the height of the Muslim revolt of the 1970s and with other atrocities committed during the Martial Law era.

The first factor recognizes that the deaths in Palimbang are innumerable. It is estimated that at least a thousand civilians were killed in the incident. Other estimates point to three thousand. The second factor involves the presence of naval vessels in the Palimbang area which were responsible for herding, detaining, and killing its residents. This naval presence highlights another factor that acknowledges the participation of the Philippine Navy and Army in this massacre. It does not help that the provincial governor himself plays an important role as he called on the military to report on the presence of MNLF rebels in the area. Given the complexities surrounding this military operation, the lack of available information or data on the massacre serves as another critical factor that makes this tragic event unusual. The lack of historical evidence encourages denial of the massacre. The erasure of this violence makes the process of transitional justice difficult. As such, the survivors of the Palimbang massacre have made great efforts to make their story heard.

The stories of Palimbang women highlight their hardships as they sought ways to survive this tragic encounter. Many women lost their families and their properties. The massacre of the men in the community left women at a loss and under the mercy of the violence of soldiers who took advantage of the disruption of their patriarchal community. Women’s lack of agency in the absence of their male relatives led to the sexual harassment and intimate violation of their lives. For other women, the loss of patriarchs in their community entailed making difficult decisions that forced them to let go of their traditions and beliefs just to ensure their survival. These women’s stories highlight the lack of structures that would have allowed them to freely mobilize without the help of male relatives, seek protection against the merciless soldiers who abused their power in public and intimate ways, and find ways that would immediately resolve the injustice their community experienced.

Similar to the women in Manili, Palimbang’s women are using their stories to find justice. Through the painful recollection of this massacre, the women of Palimbang are hoping that their violators would be held accountable and that their stories and experiences would not be erased or denied in our national history. The recognition of the massacre by the Comission on Human Rights is an important step towards their healing (“On the Recognition of the Palimbang/Tacbil Massacre and Its Commemoration Every 24th September” 2019). Hopefully, the process of transitional justice would give these women the support they would need to live peaceful lives or survive conflict should another violent confrontation arise in their area. Mindanao continues to be a rife with armed tension. Ensuring that these women are given access to various structures that would allow them to easily mobilize away from danger, safely report abusive practices, and find trust in political structures that ensures justice will be served will be helpful in the process of achieving transitional justice for women in Palimbang.

Bibliography

Abat, Fortunato U. 1993. The Day We Nearly Lost Mindanao: The CEMCOM Story : How CEMCOM Checked the Secessionist Attempt to Establish a de Facto Bangsa Moro Republic in Cotabato. San Juan, Metro Manila: F.U. Abat.

Abat, Fortunato U. 1999. The Day We Nearly Lost Mindanao. San Juan: FCA, Incorporated.

Abinales, P. N. 2000. Making Mindanao: Cotabato and Davao in the Formation of the Philippine Nation-State. Ateneo University Press.

Amaral, A. E. 2015. The Awakening of Milbuk: Diary of a Missionary Priest. Bloomington: AuthorHouse.

Calamba, Romeo, dir. 2016. CHR Martial Law Project Files - Palimbang (Mga Kwento Sa Malisbong). Documentary.

Canoy, Reuben R. 1979. “Real Autonomy: The Answer to the Mindanao Problem.” Philippine Sociological Review 27 (4): 295–302.

George, T.J.S. 1980. Revolt in Mindanao. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Gowing, Peter Gordon. 1980. Muslim Filipinos - Heritage and Horizon. 2nd Ed. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Lison Sr., Enrique. 2021. Intervew with Enrique Lison Sr.

Llana, Wareb. 2021. Intervew with Wareb Llana.

Mangakoy, Ebok. 2021. Intervew with Ebok Mangakoy.

Mangansakan II, Gutierrez, dir. 2016. Forbidden Memory. Drama.

“On the Recognition of the Palimbang/Tacbil Massacre and Its Commemoration Every 24th September.” 2019. Resolution CHR (V) No. AM2019-183. Quezon City: Comission on Human Rights.

Piang, Mohamed Panet M. 2021. Intervew with Mohamad Panet M. Piang.

All Rights Reserved | Weaving Women's Voices